TIMOTHY CASEY, tcasey at legalmomentum.org

TIMOTHY CASEY, tcasey at legalmomentum.org

Director of the Women & Poverty Program at Legal Momentum, Casey just wrote the report “Too Little Progress” [PDF] about the war on poverty after 50 years.

ALICE O’CONNOR, aoconnor at history.ucsb.edu

Author of Poverty Knowledge: Social Science, Social Policy and the Poor in Twentieth Century U.S. History, O’Connor just wrote the piece “The War on Poverty at Fifty.” She said today: “The War on Poverty remains one of the most embattled — and least understood — of Great Society initiatives. Contrary to conservative detractors, the War on Poverty did not create ‘special privileges’ for the poor. Still less was it a vast expansion of ‘dependency’-inducing cash relief, relying far more on preventative health, nutrition, and old-age related expenditures to shore up the federal safety net and on signature programs such as Head Start, Job Corps, and community-based housing and economic development to create opportunities…

“More controversially, community action programs encouraged poor people to organize for basic rights that better-off Americans had come to expect as citizens of the world’s most affluent democracy and beneficiaries of the New Deal welfare state: to decent job and educational opportunities, fair labor standards, protections against economic insecurity, legal representation, and access to political participation, starting with the right to vote. For this the War on Poverty earned the enmity of a wide array of politically-entrenched constituencies, especially in the Jim Crow South. …

“LBJ’s policies did not end poverty. … But that shouldn’t keep us from drawing lessons from its shortcomings as well as its accomplishments in building a progressive campaign against inequality. One is the importance of fighting the battle at the level of economic policy and structural reform rather than relying on redistributive social welfare policies alone. A second is that the problem of poverty cannot be resolved without addressing the deeper inequities of race, class, gender, geography, and power. … Third is that some of the fiercest battles of the War on Poverty were fought locally, as they continue to be today. … And fourth is the need to dethrone the narrative of failure…to recognize not just the capacity, but the political and moral imperative of committing the resources of democratic government to achieving a just and equitable economy.” O’Connor is professor of history at the University of California Santa Barbara.

ANNELISE ORLECK, annelise.orleck at dartmouth.edu

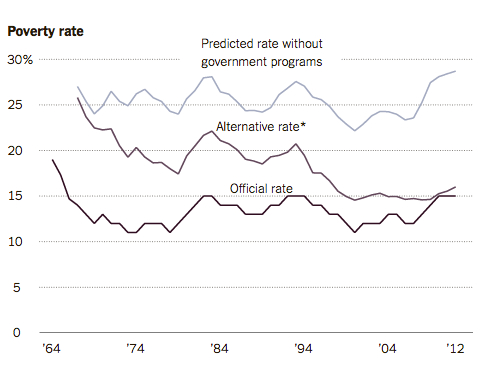

Orleck is co-editor of The War on Poverty A New Grassroots History, 1964-1980 and author of Storming Caesar’s Palace: How Black Mothers Fought Their Own War on Poverty. She said today: “Many — especially on the right — claim that the war on poverty failed. However, the fact is that it cut the child poverty rate in half in only ten years. The poverty rate has gone up and down but there is a direct correlation between poverty rates and the robustness of federal anti-poverty programs. … As a result, poverty rates have never reached the levels they were at prior to the enactment of the Economic Opportunity Act in 1964.

“The ‘great recession’ that began in 2008 would have caused infinitely more suffering if we did not have the food, shelter and income relief programs initiated under Lyndon Johnson and expanded under Richard Nixon and Jimmy Carter.

“Another key accomplishment of the war on poverty was that it expanded the political class. Poor people who had long been excluded from the political process fought for and got seats on housing, school and welfare boards. They also ran for office in local, state and even in federal elections. I would argue that the massive enlistment of poor people in the political process is one reason why conservatives are so anxious to view the war on poverty as a failure. Perhaps the more accurate view is that it succeeded all too well.”